- Choose your Country

- Choose your Country

Caravaggio

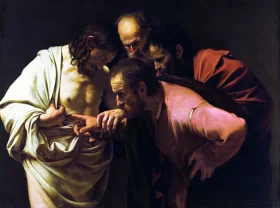

Michelangelo Merisi (Michele Angelo Merigi or Amerighi) da Caravaggio, known as simply Caravaggio (29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610) leading Italian painter of the late 16th and early 17th centuries who became famous for the intense and unsettling realism of his large-scale religious works. His paintings have been characterized by art critics as combining a realistic observation of the human state, both physical and emotional, with a dramatic use of lighting, which had a formative influence on Baroque painting.

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi or Amerighi) was born in Milan, where his father, Fermo (Fermo Merixio), was a household administrator and architect-decorator to the Marchese of Caravaggio, a town 35 km to the east of Milan and south of Bergamo. In 1576 the family moved to Caravaggio (Caravaggius) to escape a plague that ravaged Milan, and Caravaggio’s father and grandfather both died there on the same day in 1577. Caravaggio’s mother died in 1584, the same year he began his four-year apprenticeship to the Milanese painter Simone Peterzano, described in the contract of apprenticeship as a pupil of Titian Vecellio. Caravaggio appears to have stayed in the Milan-Caravaggio area after his apprenticeship ended.

Following his initial training under Simone Peterzano, in 1592 Caravaggio left Milan for Rome, in flight after “certain quarrels” and the wounding of a police officer. The young artist arrived in Rome “naked and extremely needy… without fixed address and without provision… short of money.” During this period he stayed with the miserly Pandolfo Pucci, known as “monsignor Insalata”. A few months later he was performing hack-work for the highly successful Giuseppe Cesari, Pope Clement VIII’s favourite artist, “painting flowers and fruit” in his factory-like workshop.

According to Bellori, Caravaggio resented the restriction to such lowly subject matter. Known works from this period include a small Boy Peeling a Fruit (his earliest known painting), a Boy with a Basket of Fruit, and the Young Sick Bacchus, supposedly a self-portrait done during convalescence from a serious illness that ended his employment with Cesari. All three demonstrate the physical particularity for which Caravaggio was to become renowned: the fruit-basket-boy’s produce has been analysed by a professor of horticulture, who was able to identify individual cultivars right down to “…a large fig leaf with a prominent fungal scorch lesion resembling anthracnose (Glomerella cingulata).” Boy with a Basket of Fruit and Self-Portrait as Bacchus (also called Sick Bacchus) were expropriated from Cesari by Scipione Borghese, the papal nephew, in the early 1600s and have remained in the Borghese collection ever since.

The artist’s time with Cesari appears to have ended badly, with an obscure accident involving a kick from a horse that left Caravaggio in the hospital of Santa Maria della Consolazione. At this point he forged some extremely important friendships, with the painter Prospero Orsi, the architect Onorio Longhi, and the sixteen-year-old Sicilian artist Mario Minniti.

Prospero Orsi, a painter of grotesques, who (according to Bellori) encouraged Caravaggio to strike out on his own and paint directly for the market. Baglione adds that Caravaggio painted a number of self-portraits at that time—now presumed lost. The Fortune Teller, his first composition with more than one figure, shows a boy, likely Minniti, having his palm read by a gypsy girl, who is stealthily removing his ring as she strokes his hand. The theme was quite new for Rome, and proved immensely influential over the next century and beyond. This, however, was in the future: at the time, Caravaggio sold it for practically nothing. The Cardsharps – showing another naïve youth of privilege falling the victim of card cheats—is even more psychologically complex, and perhaps Caravaggio’s first true masterpiece. Like The Fortune Teller, it was immensely popular, and over 50 copies survive.

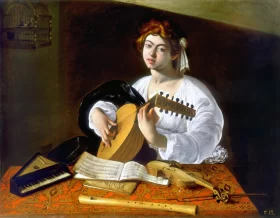

More importantly, it attracted the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, one of the leading connoisseurs in Rome. For Del Monte and his wealthy art-loving circle, Caravaggio executed a number of intimate chamber-pieces – The Musicians, The Lute Player, a tipsy Bacchus, and an allegorical but realistic Boy Bitten by a Lizard; you could almost hear the boy scream, and it was all done meticulously.” The subject is dramatic, as might be expected of a work intended to pique the interest of Roman connoisseurs: a young man in a state of undress, picking at a bowl of fruit, is rudely interrupted by a lizard that bites his finger. It may have been intended as a parable of the punishments that attend the lascivious, with the snapping lizard symbolizing the pains of venereal disease.

Caravaggio’s first paintings on religious themes returned to realism, and the emergence of remarkable spirituality. The first of these was the Penitent Magdalene, showing Mary Magdalene at the moment when she has turned from her life as a courtesan and sits weeping on the floor, her jewels scattered around her. “It seemed not a religious painting at all … a girl sitting on a low wooden stool drying her hair … Where was the repentance … suffering … promise of salvation?” It was understated, in the Lombard manner, not histrionic in the Roman manner of the time. It was followed by others in the same style: Saint Catherine; Martha and Mary Magdalene; Judith Beheading Holofernes; Sacrifice of Isaac; Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy; and Rest on the Flight into Egypt. These works, while viewed by a comparatively limited circle, increased Caravaggio’s fame with both connoisseurs and his fellow artists. But a true reputation would depend on public commissions, and for these it was necessary to look to the Church.

Encouraged by del Monte, Caravaggio painted two of his most teasingly original pictures of the mid-to-late 1590s for the Medici grand duke of Tuscany: Bacchus and Head of the Medusa. Each is a subtle jeu d’esprit. The Bacchus, for which Caravaggio’s moonfaced friend, the Sicilian painter Mario Minniti, acted as model, has been interpreted as a depiction of a male prostitute in down-at-heel lodgings offering a prospective client a glass of wine. But on closer examination, the boy’s thoughtful expression and his attributes—vine-leaf wreath, another of the artist’s baskets of fruit in which worm-holed apples and salvific grapes are mingled, carafe of wine—indicate that the figure is Bacchus in his guise as a prefiguration of Christ, offering not the pleasures of vice but eternal salvation. It is the kind of picture that Ottavio Cardinal Paravicino may have had in mind when he referred to Caravaggio, in a letter of 1603, working “in that middle area, between the sacred and the profane.”

Caravaggio liked to go around “in the company of his young friends, mostly brash, swaggering fellows—painters and swordsmen—who lived by the motto nec spe, nec metu, ‘without hope, without fear.’ ” His friends included the painters Orsi, Minniti, and Orazio Gentileschi as well the architect Onorio Longhi, a man so hot-tempered that he would be described by a later biographer as having “a head that smoked.” Caravaggio also associated with a number of Rome’s prostitutes and courtesans, notably Fillide Melandroni, a woman from Siena who served as his model for a number of pictures painted in the late 1590s: Martha and Mary Magdalene; the startlingly sadistic-erotic Judith Beheading Holofernes, in which she saws at the neck of the tyrant with her sword in a setting more reminiscent of a Roman bordello than the Assyrian general’s tent described in the Apocrypha; and the haunting Saint Catherine of Alexandria, shown embracing the sword of her own martyrdom with the tenderness of a lover’s caress.

In 1599, presumably through the influence of Del Monte, Caravaggio was contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The two works making up the commission, The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and The Calling of Saint Matthew, delivered in 1600, were an immediate sensation. Thereafter he never lacked commissions or patrons. Caravaggio went on to secure a string of prestigious commissions for religious works featuring violent struggles, grotesque decapitations, torture and death. Most notable and technically masterful among them was The Taking of Christ (circa 1602) for the Mattei family, only rediscovered in the early 1990s, in Ireland, after two centuries unrecognised.

His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel, featuring the saint as a bald peasant with dirty legs attended by a lightly clad over-familiar boy-angel, was rejected and a second version had to be painted as The Inspiration of Saint Matthew. Similarly, The Conversion of Saint Paul was rejected, and while another version of the same subject, the Conversion on the Way to Damascus, was accepted, it featured the saint’s horse’s haunches far more prominently than the saint himself, prompting this exchange between the artist and an exasperated official of Santa Maria del Popolo: “Why have you put a horse in the middle, and Saint Paul on the ground?” “Because!” “Is the horse God?” “No, but he stands in God’s light!”

Other works included Entombment, the Madonna di Loreto (Madonna of the Pilgrims), the Grooms’ Madonna, and The Death of the Virgin commissioned in 1601 by a wealthy jurist for his private chapel in the new Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala, was rejected by the Carmelites in 1606. Caravaggio’s contemporary Giulio Mancini records that it was rejected because Caravaggio had used a well-known prostitute as his model for the Virgin. Giovanni Baglione, another contemporary, tells that it was due to Mary’s bare legs – a matter of decorum in either case.

Sometime during the first half of 1601, Caravaggio left the household of Cardinal del Monte—although he remained under his protection, as he would assert more than once during his several appearances in court—to take up residence with the powerful Mattei family, who lived in a honeycomb of interconnected residences built over the ancient Roman Teatro di Balbo. Caravaggio lived in the palace of Girolamo Cardinal Mattei, painting a number of pictures for him and his two brothers, Ciriaco and Asdrubale. These included two of his most-brilliant devotional paintings, The Supper at Emmaus and The Betrayal of Christ.

Caravaggio continued to work at secular commissions during that period, painting a highly erotic depiction of Cupid surrounded by the tumbled attributes of science, art, music, and military might, entitled Amor Vincit Omnia.

In 1604 he was arrested, variously, for assaulting a waiter who had served him with a plate of artichokes dressed in butter rather than oil; for throwing stones in the street in the company of, among others, a perfume maker and some prostitutes; and for telling a policeman who was attempting to release him quietly, even though he was carrying a sword and dagger, that “you can stick it up your arse.” In between committing those crimes and misdemeanours, he painted the austere and monumental altarpiece of The Entombment of Christ for the Oratorian church of Santa Maria in Vallicella, in Rome.

The pattern continued into 1605. In early summer he completed his altarpiece of The Madonna of Loreto, popularly known as “The Madonna of the Pilgrims,” for the Cavalletti Chapel in the Roman church of Sant’Agostino. The sweetest and most overtly sentimental of his major religious pictures, it was greeted with such enthusiasm by the mass of Rome’s pilgrims who gathered to see it that Giovanni Baglione compared the sound of their collective approbation to “the cackling of geese.” At the end of 1605, Caravaggio signed a contract to paint an altarpiece for the chapel of the papal grooms in St. Peter’s. He completed the work, The Madonna of the Palafrenieri, sometimes known as “The Madonna of the Serpent,” on April 8, 1606. Not more than a month later, it was removed from view because, according to Bellori, it was considered “offensive.”

Shortly afterward Caravaggio completed the last of his great altarpieces for Roman churches, The Death of the Virgin. Austere, solemn, tragic in its very mundanity, the work shows the Apostles lamenting the death of Mary in the poorest of homes. In the words of the 20th-century art historian Roberto Longhi, it resembles “a death in a night refuge.” It is among the most-powerful and moving of Caravaggio’s paintings, but once more, not long after being installed in the Carmelite church for which it had been commissioned, Santa Maria della Scala, it was removed from public view.

Shortly after that setback, on the evening of May 28, 1606, the long-smouldering animosity between Ranuccio Tomassoni and Caravaggio flared up into a formal duel, which took place on the tennis court of the French ambassador to Rome. Caravaggio pierced his opponent’s femoral artery with his dueling sword, causing him to bleed to death in a very short time. The nature of the injury, close to Tomassoni’s groin, may suggest that Caravaggio intended to wound his opponent sexually. Wounds were meaningful in the honour culture of the time, so, for example, a facial wound might be inflicted to avenge an insult to reputation, or loss of face, while a genital wounding or attempted castration might mark a dispute over a woman. Caravaggio and Tomassoni may still have been competing over Fillide Melandroni, or perhaps they had argued over Tomassoni’s wife—the presence of Tomassoni’s two brothers-in-law as seconds gives some credence to the latter hypothesis. Whatever the cause, the killing would have a profound effect on the rest of Caravaggio’s life. He fled Rome in its immediate aftermath. Duels themselves were against the law, and thus committing murder during a duel was a grievous offense. He was convicted in absentia of murder and made subject to a bando capitale, a capital sentence, which meant that anyone in the Papal States had the right to kill him with impunity in exchange for a reward. If they were unable to produce his body, his severed head would suffice.

Following the death of Tomassoni, Caravaggio fled first to the estates of the Colonna family south of Rome, then on to Naples, where Costanza Colonna Sforza, widow of Francesco Sforza, in whose husband’s household Caravaggio’s father had held a position, maintained a palace. In Naples, outside the jurisdiction of the Roman authorities and protected by the Colonna family, the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous in Naples.

He painted one of his most-impressive altarpieces for the Neapolitan confraternity of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, devoted to the care of the sick and the poor. The Seven Acts of Mercy is a tall, dark, claustrophobically congested composition, in which the nominal seven good deeds, ranging from burial of the dead to clothing of the naked, are performed in a world so squeezed and teeming that it resembles some dark corner of Naples itself, the most famously crowded city in Italy. Three other altarpieces are associated with Caravaggio’s time in the city: a harrowingly direct Flagellation of Christ, a harsh and brutally simplified Crucifixion of St. Andrew, and The Madonna of the Rosary, a picture so sweet in mood and so awkwardly theatrical that he probably painted it earlier in his career, around 1603–04, and took it to Naples with him from Rome.

From Naples Caravaggio traveled to Malta, where he hoped to join the feared and respected Knights of the Order of St. John (or Hospitallers), Christian soldiers waging guerrilla warfare against the forces of Islam from their island fortress in the Mediterranean. To be accepted into the order would mean automatic pardon for the murder he had committed in Rome and therefore redemption from his sins. Major works from his Malta period include the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, his largest ever work, and the only painting to which he put his signature, Saint Jerome Writing (both housed in Saint John’s Co-Cathedral, Valletta, Malta) and a Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page, as well as portraits of other leading Knights.

Yet, by late August 1608, he was arrested and imprisoned, likely the result of yet another brawl, this time with an aristocratic knight, during which the door of a house was battered down and the knight seriously wounded. Caravaggio was imprisoned by the Knights at Valletta, but he managed to escape, By December, he had been expelled from the Order “as a foul and rotten member”, a formal phrase used in all such cases.

Caravaggio made his way to Sicily where he met his old friend Mario Minniti, who was now married and living in Syracuse. In Syracuse and Messina Caravaggio continued to win prestigious and well-paid commissions. Among other works from this period are Burial of St. Lucy, The Raising of Lazarus, and Adoration of the Shepherds.

After only nine months in Sicily, by the autumn of 1609, Caravaggio had returned to Naples, where he stayed once more at the Colonna Palace, painting a now-lost altarpiece of The Raising of Lazarus for a chapel in the church of Sant’Anna dei Lombardi that was later destroyed in an earthquake. Soon after finishing that picture, he was attacked by four men outside the Osteria del Cerriglio, a Neapolitan tavern of ill repute, and so severely wounded in the face that he remained close to death for several months.

He painted a Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (Madrid), showing his own head on a platter, and sent it to de Wignacourt as a plea for forgiveness. Perhaps at this time, he painted also a David with the Head of Goliath, showing the young David with a strangely sorrowful expression gazing on the severed head of the giant, which is again Caravaggio. This painting he may have sent to his patron, the unscrupulous art-loving Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of the pope, who had the power to grant or withhold pardons. Caravaggio hoped Borghese could mediate a pardon, in exchange for works by the artist.

Caravaggio created his last two paintings in 1610, while he was attempting to recover from the attack: The Denial of Peter and The Martyrdom of St. Ursula. Both are painted in such a shaky, attenuated version of Caravaggio’s robust late manner as to suggest that he was suffering from some form of terrible tremor, or perhaps an eye complaint.

News from Rome encouraged Caravaggio, and in the summer of 1610 he took a boat northwards to receive the pardon, which seemed imminent thanks to his powerful Roman friends. With him were three last paintings, the gifts for Cardinal Scipione. What happened next is the subject of much confusion and conjecture, shrouded in much mystery.

Caravaggio set off for Rome in a felucca, or skiff, laden with several paintings that he hoped to offer to Borghese in exchange for arranging his reprieve. His destination was the port of Palo, a staging post where he might hire a wagon to complete his journey by land. For reasons that remain unexplained—papers not in order, or perhaps a disagreement with the captain of the garrison there—he was arrested and detained at Palo. His paintings were carried away on the felucca, which traveled on with its other passenger or passengers to its final destination of Porto Ercole, a small harbour town on the coast of Tuscany, some 50 miles (80.5 km) north. Caravaggio paid his way out of jail and rode post to Porto Ercole. With a change of horse, he may have covered the distance in a day or a little longer. He made it to Porto Ercole but died soon after arriving there, probably on July 18 or 19, at the age of 38. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

Caravaggio had a fever at the time of his death, and what killed him was a matter of controversy and rumour at the time, and has been a matter of historical debate and study since. Contemporary rumors held that either the Tommasoni family or the Knights had him killed in revenge. Vatican documents released in 2002 support the theory that the wealthy Tommasoni family had him hunted down and killed as a vendetta for Caravaggio’s murder of gangster Ranuccio Tommasoni, in a botched attempt at castration after a duel over the affections of model Fillide Melandroni.

Caravaggio’s innovations inspired the Baroque, but the Baroque took the drama of his chiaroscuro without the psychological realism. While he directly influenced the style of the artists mentioned above, and, at a distance, the Frenchmen Georges La Tour and Simon Vouet, and the Spaniard Giuseppe Ribera, within a few decades his works were being ascribed to less scandalous artists, or simply overlooked. The Baroque, to which he contributed so much, had evolved, and fashions had changed, but perhaps more pertinently Caravaggio never established a workshop as the Carracci did, and thus had no school to spread his techniques. Nor did he ever set out his underlying philosophical approach to art, the psychological realism that may only be deduced from his surviving work.

In October 1969, two thieves entered the Oratory of Saint Lawrence in Palermo, Sicily, and stole Caravaggio’s Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence from its frame. Experts estimated its value at $20 million. Following the theft, Italian police set up an art theft task force with the specific aim of re-acquiring lost and stolen art works. Since the creation of this task force, many leads have been followed regarding the Nativity. Former Italian mafia members have stated that Nativity with St. Francis and St. Lawrence was stolen by the Sicilian Mafia and displayed at important mafia gatherings. Former mafia members have said that the Nativity was damaged and has since been destroyed.The whereabouts of the artwork are still unknown. A reproduction currently hangs in its place in the Oratory of San Lorenzo.

Read moreShowing all 78 results