- Choose your Country

- Choose your Country

바로크

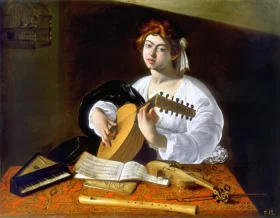

Beginning around the year 1600, the demands for new art resulted in what is now known as the Baroque. The canon promulgated at The Council of Trent (1545-63) by which the Roman Catholic Church addressed the representational arts by demanding that paintings and sculptures in church contexts should speak to the illiterate rather than to the well-informed, is customarily offered as an inspiration of the Baroque, which appeared, however, a generation later. This turn toward a populist conception of the function of ecclesiastical art is seen by many art historians[weasel words] as driving the innovations of Caravaggio and the Carracci brothers, all of whom were working in Rome at that time.

The appeal of Baroque style turned consciously from the witty, intellectual qualities of 16th century Mannerist art to a visceral appeal aimed at the senses. It employed an iconography that was direct, simple, obvious, and dramatic. Baroque art drew on certain broad and heroic tendencies in Annibale Carracci and his circle, and found inspiration in other artists such as Caravaggio, and Federico Barocci nowadays sometimes termed ‘proto-Baroque’.

Germinal ideas of the Baroque can also be found in the work of Michelangelo and Correggio.

Some general parallels in music make the expression “Baroque music” useful. Contrasting phrase lengths, harmony and counterpoint ousted polyphony, and orchestral color made a stronger appearance. (See Baroque music.) Similar fascination with simple, strong, dramatic expression in poetry, where clear, broad syncopated rhythms replaced the enknotted elaborated metaphysical similes employed by Mannerists such as John Donne and imagery that was strongly influenced by visual developments in painting, can be sensed in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, a Baroque epic.

Though Baroque was superseded in many centers by the Rococo style, beginning in France in the late 1720s, especially for interiors, paintings and the decorative arts, Baroque architecture remained a viable style until the advent of Neoclassicism in the later 18th century. A prominent example, the Neapolitan palace of Caserta, a Baroque palace (though in a chaste exterior) that was not even begun until 1752. Critics have given up talking about a “Baroque period”.

In paintings, Baroque gestures are broader than Mannerist gestures: less ambiguous, less arcane and mysterious, more like the stage gestures of opera, a major Baroque artform. Baroque poses depend on contrapposto (“counterpoise”), the tension within the figures that moves the planes of shoulders and hips in counterdirections. It made the sculptures almost seem like they were about to move.

Art historians, often Protestant ones, have traditionally emphasized that the Baroque style evolved during a time in which the Roman Catholic Church had to react against the many revolutionary cultural movements that produced a new science and new forms of religion-the Reformation. It has been said that the monumental Baroque is a style that could give the papacy, like secular absolute monarchies, a formal, imposing way of expression that could restore its prestige, at the point of becoming somehow symbolic of the Catholic Reformation. Whether this is the case or not, it was successfully developed in Rome, where Baroque architecture widely renewed the central areas with perhaps the most important urbanistic revision during this period of time.

A defining statement of what Baroque signifies in painting is provided by the series of paintings executed by Peter Paul Rubens for Marie de Medici at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris (now at the Louvre), in which a Catholic painter satisfied a Catholic patron: Baroque-era conceptions of monarchy, iconography, handling of paint, and compositions as well as the depiction of space and movement.

There were highly diverse strands of Italian baroque painting, from Caravaggio to Cortona, both approaching emotive dynamism with different styles. Another frequently cited work of Baroque art is Bernini’s Saint Theresa in Ecstasy for the Cornaro chapel in Saint Maria della Vittoria, which brings together architecture, sculpture, and theatre into one grand conceit.

The later Baroque style gradually gave way to a more decorative Rococo, which, through contrast, further defines Baroque.

The intensity and immediacy of baroque art and its individualism and detail-observed in such things as the convincing rendering of cloth and skin textures-make it one of the most compelling periods of Western art.

A rather different art developed out of northern realist traditions in 17th century Dutch Golden Age painting, which had very little religious art, and little history painting, instead playing a crucial part in developing secular genres such as still life, genre paintings of everyday scenes, and landscape painting. While the Baroque nature of Rembrandt’s art is clear, the label is less use for Vermeer and many other Dutch artists. Flemish Baroque painting shared a part in this trend, while also continuing to produce the traditional categories.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word baroque is derived from the Portuguese word “barroco”, Spanish “barroco”, or French “baroque”, all of which refer to a “rough or imperfect pearl”, though whether it entered those languages via Latin, Arabic, or some other source is uncertain. In informal usage, the word baroque can simply mean that something is “elaborate”, with many details, without reference to the Baroque styles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The word “Baroque”, like most periodic or stylistic designations, was invented by later critics rather than practitioners of the arts in the 17th and early 18th centuries. It is a French transliteration of the Portuguese phrase “perola barroca”, which means “irregular pearl”, and natural pearls that deviate from the usual, regular forms so they do not have an axis of rotation are known as “baroque pearls”. Others derive it from the mnemonic term “Baroco” denoting, in logical Scholastica, a supposedly laboured form of syllogism.

The term “Baroque” was initially used with a derogatory meaning, to underline the excesses of its emphasis. In particular, the term was used to describe its eccentric redundancy and noisy abundance of details, which sharply contrasted the clear and sober rationality of the Renaissance. It was first rehabilitated by the Swiss-born art historian, Heinrich Wolfflin (1864-1945) in his Renaissance und Barock (1888), Wolfflin identified the Baroque as “movement imported into mass,” an art antithetic to Renaissance art. He did not make the distinctions between Mannerism and Baroque that modern writers do, and he ignored the later phase, the academic Baroque that lasted into the 18th century. Writers in French and English did not begin to treat Baroque as a respectable study until Wolfflin’s influence had made German scholarship pre-eminent.

In modern usage, the term “Baroque” may still be used, usually pejoratively, describing works of art, craft, or design that are thought to have excessive ornamentation or complexity of line, or, as a synonym for “Byzantine”, to describe literature, computer software, contracts, or laws that are thought to be excessively complex, indirect, or obscure in language, to the extent of concealing or confusing their meaning. A “Baroque fear” is deeply felt, but utterly beyond daily reality.

Read more1–100/682개 결과 표시